“The bourgeois era, with its false and misleading concept of humanity, is over. A hard century has dawned. No one can master it with meekness but only with manliness and strength. The world is divided into lovers and haters. Only he who stands on solid ground knows exactly when to love and when to hate.”

From an editorial written by Joseph Goebbels on 6 September 1942 in the Berlin-based Nazi weekly Das Reich

In a few different contexts, during lectures and workshops I have led, and during other social meetings, I have been asked if anyone has thought about whether they could have developed into terrorists, loaded not only with weapons but also with feelings of hatred towards other people. Somewhat surprisingly, most have answered that they absolutely could not imagine it.

Their self-images, carefully taught in the culture we have been in, have been framed and coloured by the idea that as a citizen of a society with a reasonably high average level of education and with an openness based on ideals of equality and democratic openness, one is protected from being filled with hateful feelings. It was like putting the key in the door to pretty unexplored areas of people’s inner images of reality and, thus, of human psychology. Do we humans have the skills and resources to build societies that are culturally advanced enough to prevent the occurrence of brutality, evil and violence? Do we? Looking at human history, there is every reason to delay the answers to such a question.

The whole of human history is deeply bloodstained. Threats, hatred, outbreaks of violence and wars run like a string of ill-gotten pearls along the course of human migration and expansion on all our continents. A study of major violent events in the 20th century alone, up to the present day, yields vast amounts of documentation of mass killings orchestrated by people with rage in their eyes. They have surfaced in all cultures: in Africa, Asia, the Middle East, South America, West Asia and Europe. Particularly in Europe, and of course, especially in Germany in the 1930s and 1940s with the most horrific extermination camps in history. However, several countries are vying for second place behind it.

Furthermore, today, we have both warlike nations and hordes of terrorist groups constantly honing their weapons, not refraining from using them. Within and between all human cultures so far, war and killing seem to be inevitable elements. Is hatred possibly embedded in our genes and DNA, and are there manufactured vaccinations against these deeply destructive processes?

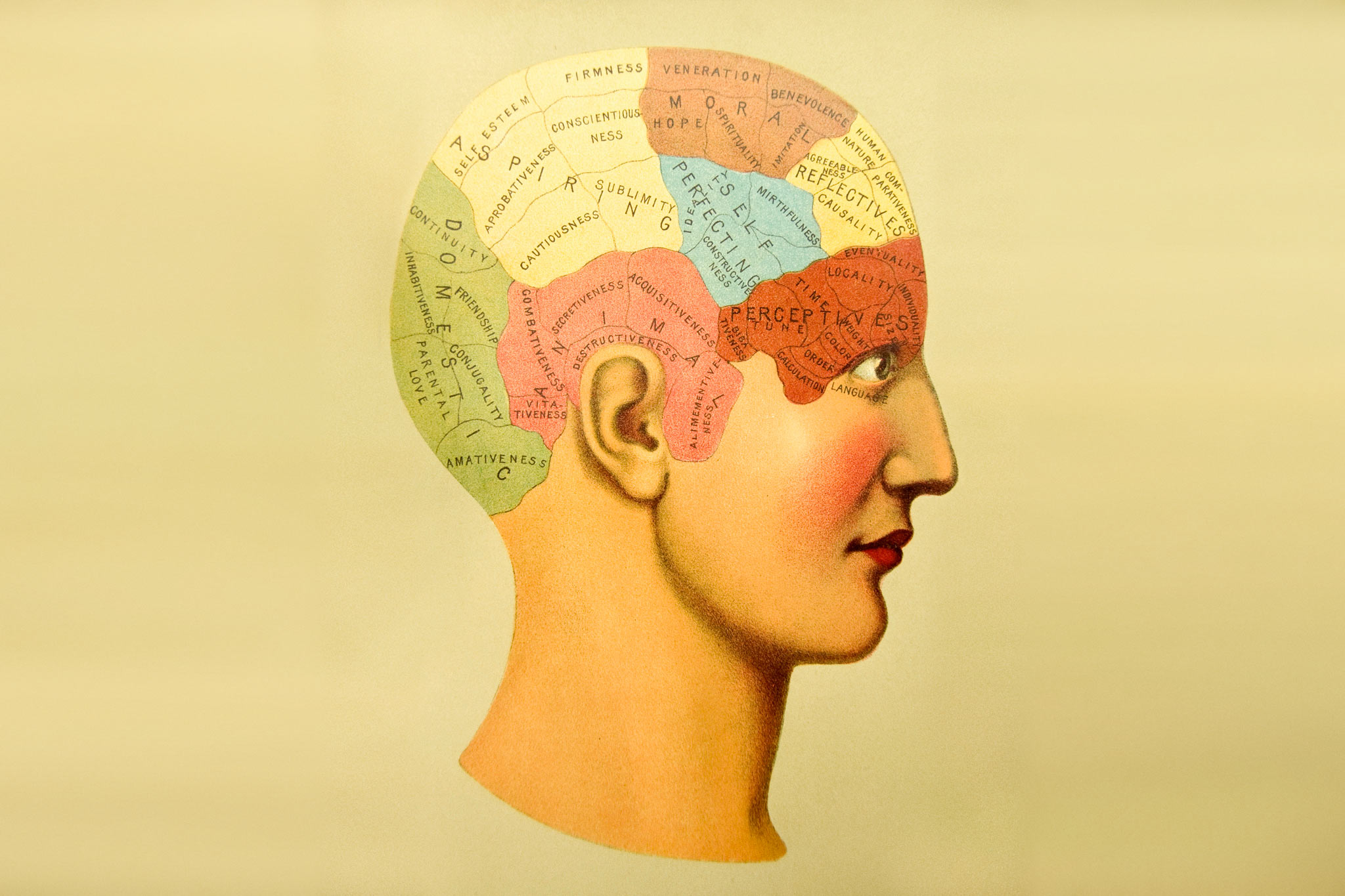

This opens the door to many fundamental studies of human evolutionary biology, human history and political ideologies, the teachings of political science regarding the formation of nations, and human neurobiological and psychological development. All this cannot be covered in a short article. I will content myself with summarising some critical aspects of classical psychology.

“There is nothing to say that humans are born with hateful and evil impulses”

There is nothing to say that humans are born with hateful and evil impulses. However, we all have genetically based drives that immediately manifest as an enormous desire-hunger. The term libido usually summarises these drives. The libido causes the infant to seek out the mother’s breast and, more or less noisily, suck in the nourishment. The libido also controls the mother’s desire to give the breast to the baby. The situation for both could be pure paradise. If not, there is always a ‘but’ in the picture. The desire is almost insatiable. It may take short breaks, but then it grows strong again, and the connection may be broken for a while or longer.

We, humans, develop early in life by not only inhaling the milk, the smells, the warmth, and all the hormonal pheromones that come from outside. We endeavour to psychologically inject or introject all the good, and make it ours. Nevertheless, since the paradisiacal is constantly changing, there will appear chains of frustrations; for example, when interruptions occur or when suddenly certain pain impulses within the body emerge, the child will be gradually filled with the complexity of life via its two sides: the desirable suitable objects and the very much undesirable harmful objects. The objects could be people or parts of people or extraordinary things or situations. All these undesired bad objects are packaged into a standard uniformity, often named ‘the other’ or ‘the others’, that both child and mother try to get rid of quickly.

A standard tool used for shuffling the undesirable objects away as far as possible is using the opposite of introjection, namely projection. What I do not want to have or be the bearer of, I place on something else or someone else. It is like an innate process that begins in infancy and usually continues through the years, often throughout life. In many adults in different societies and cultures, the forces of rejection thrive, especially towards others, those who do not look or behave like us. They are the ones who can prevent or even destroy me, if I do not avoid or destroy them first.

The force we humans are equipped with alongside the libido is usually called an aggressive force. In most cases, this force interacts with the libido and enables us to absorb, inhale, or introject what we need. With its help, we chew the food already in our mouths, and it is with its assistance that we split the wood on the log to get the heat the stove can give us. In most contexts, the aggressive force is purely beneficial, an asset in life’s journey. But the power can also be accumulated, harboured and unleashed against those who seem to threaten us, those who are not like us and whom we do not want.

“The Way of Boundlessness is outwardly almost the opposite of the Way of Authority, but can end similarly”

In all modern societies, various instruments are used to stimulate and educate citizens to fulfil the ideals that those in power would like to see around them. Population groups are offered, or forced to follow, a particular path forward, through economic, political, and ideological instruments. In Nazi Germany, this was essentially the Path of Authority. In short, it was characterised by the dictatorship of patronage. It often appeared to be almost ruthlessly harsh. The quickest and most effective way to mould the growing generation was to impose the norms and duties required by the time. Children were often forced to bend and develop themselves as best they could. It required an encapsulation of more spontaneous feelings of pleasure, where the aggressive forces were used to keep the urges locked up. The strategy was unsuccessful, as there were internal and external conflicts and contradictions.

One way of dealing with this turbulent powder keg was to develop oneself, through imitation and identification with authority figures, into a person with apparent rigidity of thought and behaviour. Other people who think and act differently became truly different and, as such, were often seen as potential enemies. This path also exists in many contemporary societies.

The Way of Boundlessness is outwardly almost the opposite of the Way of Authority, but can end similarly. The road merges with a diffuse environment; moving freely in any direction is possible. There are no directives and guidance except in very few situations. You are free! Do what you want! These feelings of freedom may be momentarily attractive, but soon, they are mixed with discomfort stemming from an underlying anxiety about being left alone. The orientation map is blurred, and most things seem unclear. The inner aggressive force can turn into an underlying hatred of everything. No rationally developed control exists because the external reality with its social instruments has never been incorporated as sustainable anchors in an unclear inner conscience.

During my previous lectures and workshops, during which I sometimes asked if anyone could imagine acting as a terrorist full of hatred and rage, this mainly resulted in negative answers. “Oh no, not me.” However, the core of the lessons was to remind everyone of each one’s attachment to the surrounding culture. All of us, both you and I, could quite quickly develop into living murder machines under special ideological and political conditions. The human history shows a lot of evidence for this kind of behaviour. There are many people out there with hearts and minds of hate.