Memories don’t just fade, as the old saying would have us believe; they also grow. What fades is the initial perception, the actual experience of the events. But every time we recall an event, we must reconstruct the memory, and with each recollection, the memory may be changed – coloured by succeeding events, other people’s recollections or suggestions, increased understanding, or a new context.

Excerpt from the book Witness for the Defence by Dr Elizabeth Loftus

Truth and reality, when seen through the filter of our memories, are not objective facts but subjective, interpretative realities. We interpret the past, correcting ourselves, adding bits and pieces, deleting uncomplimentary or disturbing recollections, sweeping, dusting, tidying things up. Thus, our representation of the past takes on a living, shifting reality, a living thing that changes shape, expands, shrinks, and expands again, an amoebalike creature with powers to make us laugh, and cry, and clench our fists. Enormous powers – powers even to make us believe in something that never happened.”

“The next turn leads us to a small town we have never visited before,” he said to his wife, sitting in the passenger seat beside him. “Let’s turn in there to have a look.”

The wife did not reply but nodded her approval.

“Look, how nice this looks,” he said. “With the whole view of the lake. I suggest we park somewhere, take a short walk and see if there’s a lovely café where we can have a coffee.”

After he pulled into a car park and they both got out of the car, the wife said they had visited the town a few years ago. She recognised herself very well.

“No, no, no,” the husband said emphatically. “We’ve never been here. At least I haven’t.”

“You have,” the wife retorted. “We’ve both been here.”

The couple’s discussion was intense but brief. The husband said that the wife had made a mistake, and the wife claimed that the husband had apparently lost his memory. They made peace by remaining silent without giving in to the other. It had to be what each of them thought. In any case, the difference did not affect the flavour of the coffee and its accompaniments. Both declared themselves satisfied, after which the car journey continued.

“One of the great mysteries of scientific psychology is how humans experience our lives and store memories of these experiences”

One of the great mysteries of scientific psychology is how humans experience our lives and store memories of these experiences. Experiences are mainly based on our internal representations of what we register through our five senses: sight, hearing, smell, taste, and touch. Sometimes, a sixth sense is added, called proprioception, which can be translated as the sense of balance and body perception.

Do we hear everything that goes on in what we call reality? The answer is no, absolutely not. Young people can perceive sounds in the full range of human hearing, between 20 Hz and 20,000 Hz (vibrations per second). It is a limited range. The equivalent hearing of dogs is between 40 Hz and 60,000 Hz. Many animals can hear even higher and/or lower sounds than this. In addition, human hearing deteriorates over the years, usually affecting high frequencies and gradually spreading to lower frequencies. For example, most people over 30 cannot perceive sounds above 18,000 Hz. Thus, the calls and songs of crickets and small birds are gradually silenced.

It is the same with our other senses. The modern metropolitan man, who mainly lives and works in our engineered technological environments, is quickly becoming increasingly depleted in his ability to correctly read all the natural, surrounding information about everything constantly happening. Even the flavour of our dishes cannot be enjoyed the same way as when we were younger. What we feel we are experiencing may no longer exist as it is. As compensation, we often activate our memories and relate to them when describing what we see, hear, smell and taste.

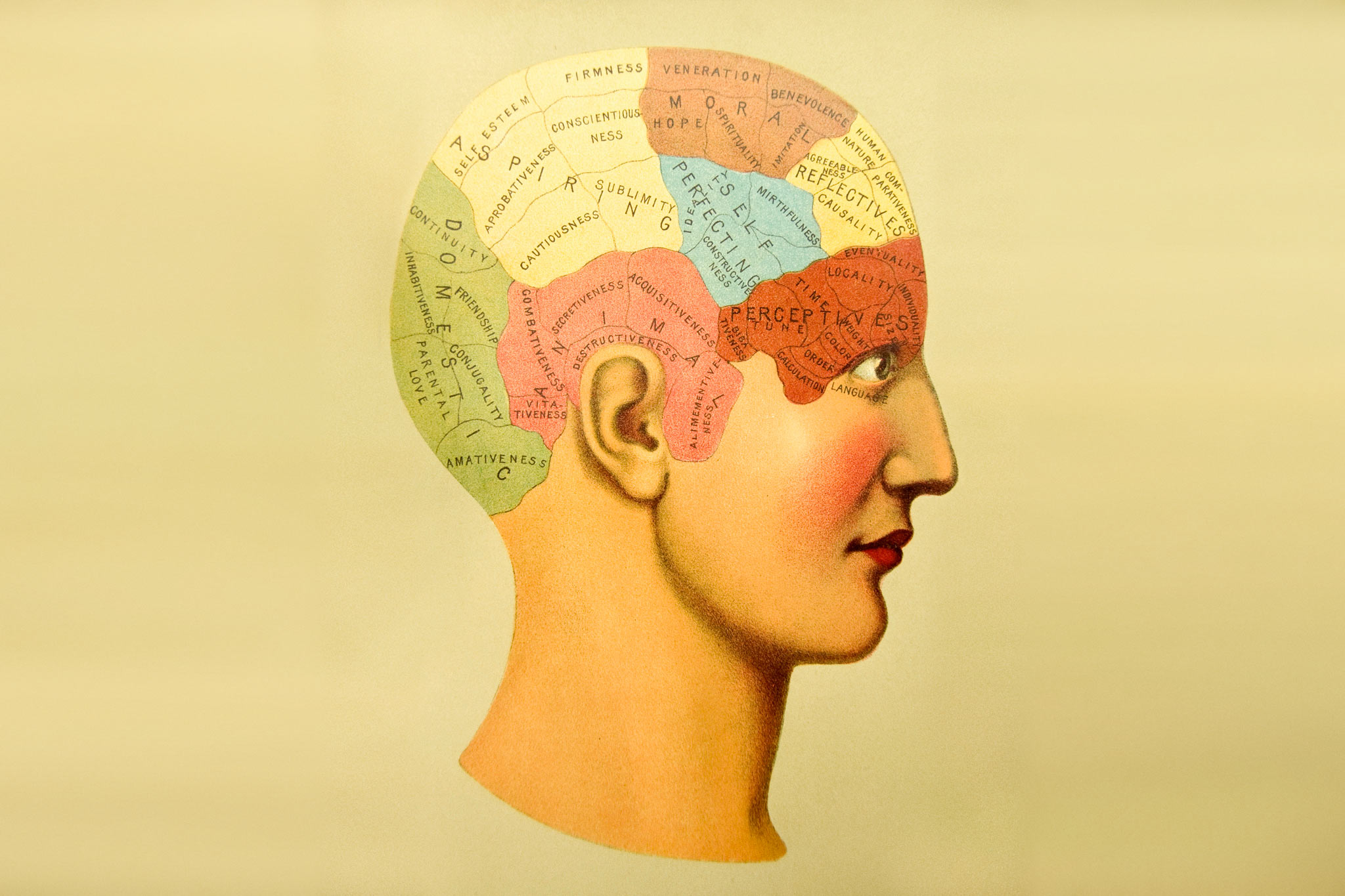

Is it then possible to trust our memories? Are they imprinted in an unchanging fact box in our brains? No, they are not. Our brains are plastic, much like soft, changeable, and living organisms beyond our control. An adult human brain consists of about 65 billion nerve cells (neurons) and almost as many protective layers (myelin) around the nerve cells. Each neuron has specific projections (dendrites) that receive signals and other projections (axons) that transmit signals. Signalling to and from neurons occurs around the clock, even when we sleep. It is done via synapses, which are the conducting contacts between dendrites and axons. The number of synapses in the still-young but biologically mature individual is almost infinite.

When we talk about our observations of the world around us, and of ourselves, being stored in the brain, we are referring to the fact that the conflicting streams of biochemical and electrical signals in different parts of the brain are activated over and over again, forming repetitive traces, which can, however, be gradually or suddenly affected and changed, by diseases, physical injuries, age-related degeneration, but also by additional, new, intense experiences. Thus, what you remember today may be adjusted and changed tomorrow. Moreover, some brain traces are easily affected, while others remain in more stubborn, persistent patterns. Those easily influenced are usually summarised as constrictions, much as if the brain steers clear of what seems less important to occupy itself with. What is perceived as more frightening and traumatising, the brain often closes the door to, something referred to as repression.

“Some brain traces are easily affected, while others remain in more stubborn, persistent patterns”

Our brains are also constantly exposed to intense communication exchanges with the environment, often without us being aware of them. One example is the hormones that everyone continually secretes through their skin, known as pheromones. Each person spreads their special odour. Scents, or rather odours, are registered by others via the sense of smell (the olfactory system) through millions of receptors within each of us. When the mother smilingly says to the child, ‘I love you’ while unconsciously releasing 780 different pheromones expressing a blissful mixture of something else, that the child’s receptors are reading at lightning speed – what happens inside the child? What takes place in the child’s brain? Probably lightning-fast bioelectrical trails that suddenly collide with each other and mainly cause confusion, whereupon the child tries to escape by closing in on itself and distancing itself from its surroundings.

Other, to us unconscious, communication systems in our social life can be even more complex and complicated. An almost gigantic field of research belongs to the so-called chaos theory and touches many academic disciplines, such as ecology, economics, physics, mathematics, medicine, meteorology, psychology and others. The so-called butterfly effect was described and coined in the late 1970s by the American mathematician and meteorologist Edvard Lorenz, who described how the butterfly’s wings in some remote place on our planet could affect air currents in ways that eventually open up for a hurricane far away somewhere else. Among other things, this has opened up interest in physics’ endeavour to understand the microcosm via quantum physics, where most of it is about energy waves that sometimes take the form of particles and sometimes continue only as waves. Light and its photons are illustrative examples of this.

Is it conceivable that an individual’s active brain activity can also orchestrate wave motion outside the body and that other individuals’ neurons can pick up these activities with their dendrites in the brain? Theoretically, it could be possible. If so, we could communicate via language, pheromone exchanges, and other energy systems that are entirely unconscious. The latter could be divided into either harmonising or non-harmonising parts. The harmonising parts would then be the building blocks for potentially good, productive ‘brain forces,’ memory banks included, while the non-harmonising ones would lead to misunderstandings, misconceptions and generally more destructive processes.

The man embraces the woman softly and intimately, whispering “I love you.” At the same time, a burst of energy-filled waves shoots out from the man’s brain and is picked up by the woman’s neurons. Unable to make sense of the concurring messages, she reacts by pulling away slightly, wearing a frown.

Could things really be working this way? I turn to an expert in the field of chaos theory, and a theoretical physicist at that, Professor Ulf Danielsson*. In some of his recent writing, the following caught my eye: “With most of what exists, we still don’t know what it is.”

*Professor Ulf Danielsson is a member of the Royal Society of Science in Uppsala/Sweden, and the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences. He was previously vice-rector of Uppsala University.