“Goodness is beautiful, so is love, but you do not build societies around emotions that belong in the private sphere and in interpersonal relationships. Our laws strive for justice, not love. Our national insurance system is not an expression of goodness, but of responsibility. We stand together in solidarity and cooperate with each other. Not because we love each other or because we are good, but because we realise that supporting each other and helping those who are vulnerable benefits everyone. In a good society, every citizen understands that their liberties end where another person’s liberties begin”

From Den banala godheten (“The Banality of Goodness”) by Ann Heberlein

I am out driving. There’s always congestion at this time of day. I read the traffic like a book. A complex book. I read the speeds and speed changes. My own and that of other drivers. Both hands are on the wheel. Right foot alternating between accelerator and brake pedal. I’m coming to the roundabout with three entrances and four exits. I’ll need to be alert. The motorists on the roundabout have the right of way. I try to read their speeds and intentions. Will they keep driving on the roundabout, or are they about to turn off? They should use their blinkers to make it easier for the stream of motorists behind them. But not many do. Most keep on going without indicating. I must wait for a big enough gap to open. Then full throttle. Blinker flashing.

The highest permitted speed on a motorway is 100 kph. I’m in the middle lane averaging 98 kph, and I am being overtaken on both sides. Overtaking on the right is not allowed on motorways, but not everyone abides by that rule. Some motorists are driving at speeds of 130–140 kph. Some are slalom-riding between the lanes without using their blinkers.

Yet, I’m not a bit surprised by what I see around me. I took my driver’s licence sixty-five years ago, so I’m no novice. I let it pass with a mutter about the lack of traffic police these days.

Traffic is an integral part of our everyday culture and doesn’t differ from any other cultural expression. The general culture of a nation or a community is reflected in the way people behave in traffic. Do they interact with each other? Do they focus as much on their fellow motorists as they do on themselves? Are they aware enough to politely leave a gap for those who want to enter the lane? Are they for or against government regulations?

When you’ve lived as long as I have, cultural experiences are filtered through a myriad of memories. The changes are discernible. There is nothing strange about that.

A society is a dynamic economic, social, and technological build that only stops progressing when those in power (usually men) slow down and reverse into an authoritarian, dictatorial and strictly conservative lane. An approach that impoverishes the culture makes it static and allows it to wither away. But that is also a form of cultural expression.

“The general culture of a nation or a community is reflected in the way people behave in traffic”

Studying car traffic is, of course, just one of many observational methods for describing a culture. In his classic novel The Plague, French-Algerian author Albert Camus (1913–1960) studied the cityscape in the Algerian city of Oran and wrote the following:

Our citizens work hard, but solely with the object of getting rich. Their chief interest is in commerce, and their chief aim in life is, as they call it, “doing business.” Naturally, they don’t eschew such simpler pleasures as lovemaking, sea bathing, going to the pictures. But, very sensibly, they reserve these pastimes for Saturday afternoons and Sundays and employ the rest of the week in making money, as much as possible. In the evening, on leaving the office, they forgather, at an hour that never varies, in the cafes, stroll the same boulevard, or take the air on their balconies. The passions of the young are violent and short-lived; the vices of older men seldom range beyond an addiction to bowling, to banquets and “socials,” or clubs where large sums change hands on the fall of a card.

With a keen-edged psychological scalpel, Camus reveals how people act during a crisis, which initiates selfishness, greed, fear, and indifference and hopeful optimism.

How does this compare with our society of today? Many, of course, work for the money. But is a bathtub full of banknotes (or digital currencies) the only vision that exists? Or do we do what we do to progress society to the benefit of everybody, not just ourselves? Is my, and possibly my close family’s, wellbeing the only inner guide for what I want to achieve, or do I have more idealistic ambitions than that for my continued life?

Hypothesis: In conversation with others on these issues, I would get an overwhelming consensus in support of society to the benefit of everybody, with solidarity as the main driving force. But what else would they say? The desire to appear reasonably kind-hearted would cover any underlying egoistic tendency in a thick blanket. Open egoism does not come across as particularly attractive during a conversation.

Anyone studying the most common human behavioural patterns is therefore recommended to supplement close conversations with analytical observations from a distance. This is when the culture shines through. And with it the inherent morality of the masses – or lack of.

Regardless of the type of society and where on the planet it is located, it will have complex built-in structures, often consisting of the endless contradictions that arise when dreams collide with legislation, hopes meet demands, and rights claim obligations.

Society is full of bubbling antagonism that puts it under constant pressure.

“Do we do what we do to progress society to the benefit of everybody, not just ourselves?”

In certain situations, it becomes easily combustible, and frustrations and discontent rise to the surface along with demands for political change. Even in calmer times, there is a constant debate on the country’s direction, a discussion that never ceases even when the debaters are forced underground.

It makes no difference if the leaders are women or men. Matriarchs are put under the same pressure as patriarchs, and the methods used to crush an uprising are the same. The police and armed forces provide the muscle, while churches and other congregations use more advanced methods.

Preachers have constantly hammered home their message under the threat of hellfire and brimstone. This method has successfully gotten entire communities to stand hat in hand, bowing and nodding instead of rebelling. History has shown that the latter is never risk-free in certain societies.

Morality and ethics could be described as a set of rules designed to dampen the waves, soften the sharp edges, and entice citizens to get along under the same umbrella.

Opinion-forming, yes, but not with a physical struggle and preferably without the use of too many harsh words. Withdrawal, yes, but not to the extent that it could lead to medical disorders.

Morality flourishes when it is carefully fertilised through the labyrinthine walkways of childhood, with parents and other guardians acting as good role models, then fortified through the school years and the ethical guidelines of the workplace. This process is known as laying a common set of values that many people hope will become a pillar of contemporary culture.

In some cases, it becomes just that. For a time. Eventually, internal and external forces will question morality in ways that enforce changes to it. These forces can invariably be linked to the desire for freedom. Most often, it is about the individual’s longing for freedom. This eternal flame breeds notions of the right to decide over one’s own body, one’s intentions, one’s dreams about one’s future, and one’s unquestionable right to be oneself.

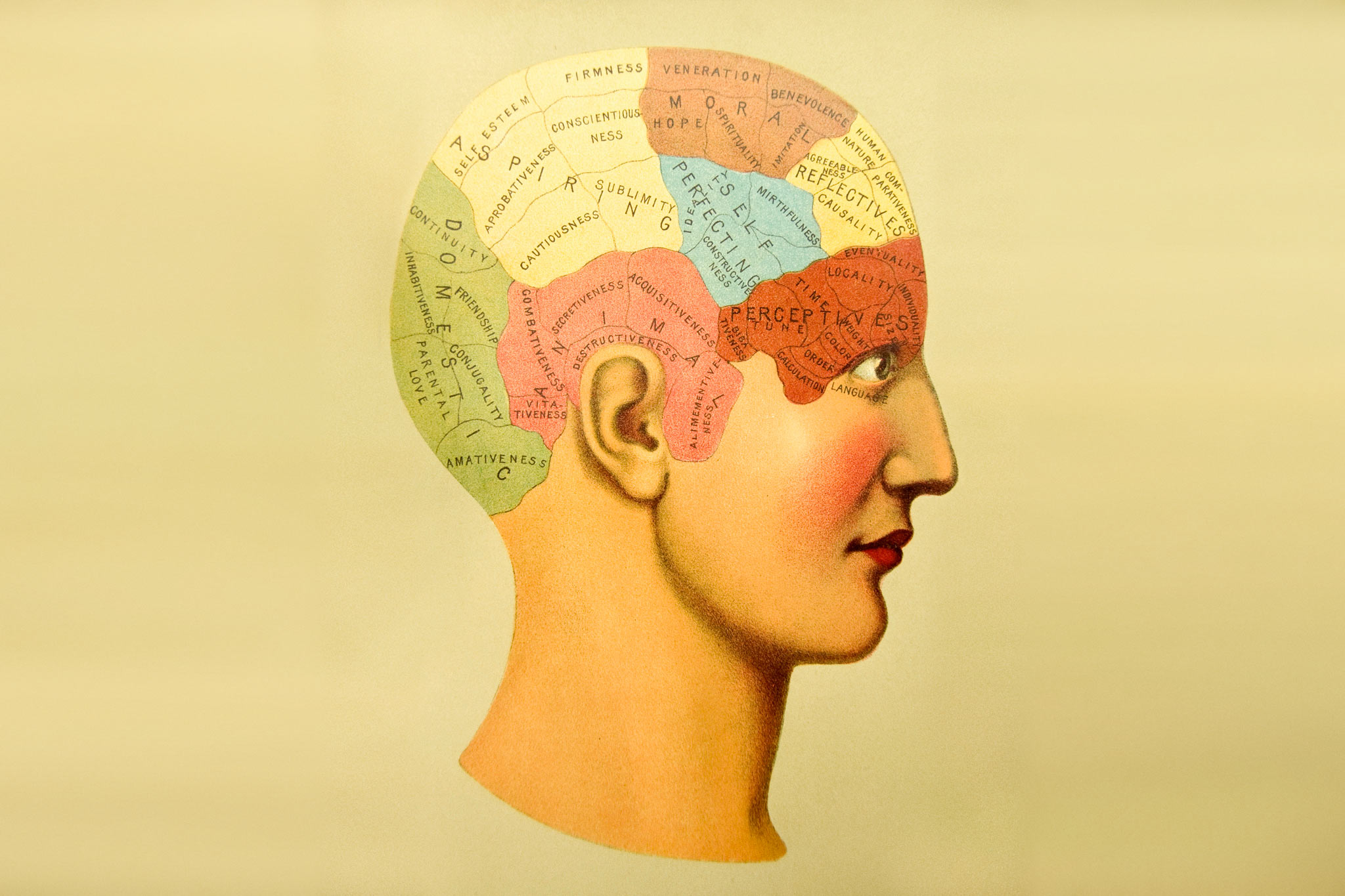

The latter, the right to be oneself, rests on the very unstable ground simply because most of us know very little about who or what we are. The awareness of oneself can, in exceptional cases, be great (after undergoing several years of psychoanalysis, perhaps), but the unconsciousness is usually greater. It is more common to navigate according to our dreams of what we would like to be or want to become, rather than who we are.

“Open egoism does not come across as particularly attractive during a conversation”

The individual’s longing for freedom seldom goes hand in hand with society’s overall goals, other than possibly in political debate. Political parties that emphasise the importance of individual liberty are always walking a tightrope.

Ordinances, laws and regulations must govern society. But, man as an individual will always struggle to adapt to moral superstructures, especially when draped in legalese. He will continuously pursue personal development while agreeing that a country must be governed by law.

At best, personal development can be achieved through the exacting standards of critical thinking combined with a constructive creation of the new, the different, the constant pushing of the boundaries. Some also find attractive channels that lead to politics or non-profit organisations.

If the need for personal development is prevented or suppressed, it will eventually lead to destructive outbursts, regressive behavioural patterns (linking back to childhood), and a distinctly egocentric attitude.

The destructive outbursts would be aimed at the common ground, the moral superstructure, and the values meant to stabilise. Here, not least via social media, gaps can open up for personal attacks and provide opportunities to attack established knowledge and scientific findings and promote conspiracy theories.

The desire to release the unbridled impulsivity that could lead to all kinds of abuse, even crime and other deviations from the accepted norm, is also part of the destructive urge. This is when tears appear in the finely woven fabric of society designed for the good of all.

Don’t forget to indicate when driving on the roundabout and when switching lanes. I could be bringing up the rear or waiting to take my place on the carousel.